Two principal dancers stood before an after-show audience gathered in the lobby of the Boston Opera House. A young man and a young woman, exhausted from over two hours’ dancing in Eugene Onegin, did their professional best and from the steps of the grand staircase looked into the upturned faces of their fans. The dancers tried to do what they had agreed to do, to speak about their understanding of the ballet in which they had just performed so gloriously. One dancer pulled a white pullover closer around her; the other stood at ease in his jeans, hands joined behind his back.

From time to time in the next fifteen minutes, the ballerina put her hand on her chest, looked up into the air above her and said haltingly, “I'm sorry. I'm just emptied right now.” It was an apology, a plea for our understanding of what she had poured out for us through her dance.

In two different scenes in the ballet, each of these principals tears a letter into pieces. In each case we understand what the letter had said, what it had offered of the heart, of the world in which someone smitten lives. In each case the returned letter is at first refused; the writer of the letter will not touch the letter even when it is thrust before them. The unwilling recipient must then shred the letter before the face of its writer if a clear refusal is to be understood.

Love in 1820s Russia was not easy.

The journalist interviewing the two dancers asked about the significance of love letters. Do actual letters, she asked the dancers, have power in them that can be matched these days by email or text messages?

The young man thought not; he confessed, however, with a smile that he had never written a love letter.

At greater length the ballerina replied that the communication of love in a written letter, a hand-written letter, is flowing from the heart through the arm into the hand that writes it. The material object, the very paper on which the message is written, is soaked in the love of the person who has written it. Nothing similar, she thought, could happen in an email, a text message or a tweet.

The audience laughed, smiled, nodded, agreed; there was nothing we would not do for this ballerina at the end of the evening.

Amid half-regretful applause, we allowed ourselves ready. We would head out. The evening was over. If the two dancers were exiting by a different door from those by which we issued onto a cold February sidewalk, the dancers likely checked their phones as automatically as we did.

We made our ways into our histories. All of us.

Which one of us had ever torn up a love letter?

How many of us would get to write one again?

Monday, February 29, 2016

Monday, February 8, 2016

What This Lent Can Be About

Last summer I stayed in a monastery guest house for three days. There was the welcome chance to hear chant sung in Latin and French and to walk the québécois countryside.

One of the places I frequented between chapel services and meals in the guest-house dining room was the gift shop. The shelves of the gift shop were lined with honeys and jams and chocolates and cider. Refrigerator cases displayed cheeses in rounds and wedges. Attention was obviously paid to expiration dates, and stock was kept fresh and fresh-looking. Over the three days I made thoughtful decisions, choosing items that matched my buying history in other settings. My purchases reflected me and what I regularly like to serve or give as gifts.

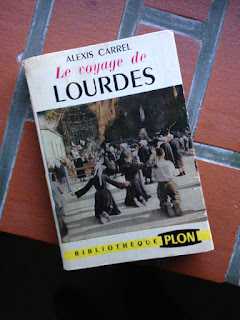

The shelves of the guest-house library offered a different kind of challenge, and what I took back to my room the first night was a soft-cover volume in French. Part of the lure of the book was that it was worn enough to assure me that it had attracted other readers since its printing in the early 1950s. The cover photograph showing pilgrims at Lourdes, their hands raised in prayer, had faded over the years; the pages were yellowed.

Familiar though I was with the story of the Marian apparitions, I was hardly what one would call a devotee of the literature of healings and testimonies. The French prose of the opening pages was clear, however, written by a medical doctor accompanying one of the standard pilgrimages into the Pyrenees in the early 1900s; the tone of the narrative was intelligent.

I decided to spend time that first night of retreat with the young doctor as he moved through the cars of the train on its way into the mountains. I read how he examined one of the gravest cases, a young woman with tuberculosis; its progress left her in increasing pain and discomfort through the night of travel. The doctor described a discoloration under her fingernails that was a sign of the irreversible onset of the death agony. Giving her morphine, he urged her to consider returning to Paris, but she was strong-willed. She intended going on with the other pilgrims and praying with them the next day at the famous grotto in Lourdes.

I was reading a narrative that the doctor had kept from publication all his life. Other writings of his would get into print, but not this tale of a healing that the doctor had witnessed and could hardly credit at first. A long skepticism, one of the characteristics that had qualified him in a special way for his work on the pilgrim journeys, drove him to spend a solitary night before the grotto where apparitions of Our Lady were said to have occurred. Be real, he begged Mary during his night in prayer, be more than a beautiful legacy of art and poetry. Make the healing of the young woman with tuberculosis a real one and a complete one.

Why does this memory from the summer visit to a monastery come to me at the approach of Lent? In earlier years I have made thoughtful decisions about how to observe this season healthily and sanely. What might this Lent be about? A hunger for what?

A life more real at times than anything I might write about it.

An experience safely beyond what can get me raising the camera, almost involuntarily taking aim as though to ensure that no one can take issue or cast doubts or dismiss what is unfolding before me and around me.

A conviction about how I might live beyond the writing and beyond the camera and beyond the setting down and serving up my story like a gift of honey, like a wedge of cheese.

Is there something ready to come into my life that I can just look up and see? Can I just look up and even not yet see it and still know how all right my life has been?

One of the places I frequented between chapel services and meals in the guest-house dining room was the gift shop. The shelves of the gift shop were lined with honeys and jams and chocolates and cider. Refrigerator cases displayed cheeses in rounds and wedges. Attention was obviously paid to expiration dates, and stock was kept fresh and fresh-looking. Over the three days I made thoughtful decisions, choosing items that matched my buying history in other settings. My purchases reflected me and what I regularly like to serve or give as gifts.

Familiar though I was with the story of the Marian apparitions, I was hardly what one would call a devotee of the literature of healings and testimonies. The French prose of the opening pages was clear, however, written by a medical doctor accompanying one of the standard pilgrimages into the Pyrenees in the early 1900s; the tone of the narrative was intelligent.

I decided to spend time that first night of retreat with the young doctor as he moved through the cars of the train on its way into the mountains. I read how he examined one of the gravest cases, a young woman with tuberculosis; its progress left her in increasing pain and discomfort through the night of travel. The doctor described a discoloration under her fingernails that was a sign of the irreversible onset of the death agony. Giving her morphine, he urged her to consider returning to Paris, but she was strong-willed. She intended going on with the other pilgrims and praying with them the next day at the famous grotto in Lourdes.

I was reading a narrative that the doctor had kept from publication all his life. Other writings of his would get into print, but not this tale of a healing that the doctor had witnessed and could hardly credit at first. A long skepticism, one of the characteristics that had qualified him in a special way for his work on the pilgrim journeys, drove him to spend a solitary night before the grotto where apparitions of Our Lady were said to have occurred. Be real, he begged Mary during his night in prayer, be more than a beautiful legacy of art and poetry. Make the healing of the young woman with tuberculosis a real one and a complete one.

Why does this memory from the summer visit to a monastery come to me at the approach of Lent? In earlier years I have made thoughtful decisions about how to observe this season healthily and sanely. What might this Lent be about? A hunger for what?

A life more real at times than anything I might write about it.

An experience safely beyond what can get me raising the camera, almost involuntarily taking aim as though to ensure that no one can take issue or cast doubts or dismiss what is unfolding before me and around me.

A conviction about how I might live beyond the writing and beyond the camera and beyond the setting down and serving up my story like a gift of honey, like a wedge of cheese.

Is there something ready to come into my life that I can just look up and see? Can I just look up and even not yet see it and still know how all right my life has been?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)